Now, this may sound like an attack on students, but it isn't. I don't blame students – well, not completely. Students are quite willing to write, especially today. All my current students write every day in countless texts, Facebook posts, and tweets, and they write all that stuff because they instinctively like to engage in conversation. It's what humans do. Everyday, all of us engage in a few conversations intensely (say, conversations about fashion, sports, politics, romance, or religion with our friends or family), and we engage in many other conversations more casually. Today's students are already writing more than at any other time in history. According to a 2016 article on the website Text Request, "In June of 2014, 561 billion text messages were sent worldwide. That’s the most recent number we’ve got. Obviously that’s a rounded figure, but it brings us to roughly 18.7 billion texts sent every day around the world." That adds up to about 7 trillion text messages a year. That is a hell of a lot of writing about nearly everything you can imagine. This generation is producing more writing per year than in all of previous human history combined, and they are doing it because they want to. No doubt about it. All students are writers already, and they like it.

So why don't most students like academic writing? I think it's mostly because they don't see academic writing as a conversation about engaging topics with interesting, engaging people. Too many students don't particularly want to talk to their professors about anthropology, botany, or zoology given that they think their profs are old, boring people and their subjects are even more boring and irrelevant to the degree they are pursuing.

Unfortunately, too few college writing courses confront this issue. We writing teachers should teach students strategies for turning any class writing assignment (from algebra to zoology) into an interesting, worthwhile conversation. In her presentation "Writing Is a Conversation," writing instructor Johannah Rodgers says that treating writing assignments as conversation has numerous benefits for students. First, it increases student's confidence in their writing, and then it makes the connections between the written conversations student already have in their social spaces with the academic conversations they engage in college. This can make for better writing and higher grades for students and better reading for teachers. That's a win-win.

So how do you go about framing your academic documents as a conversation? I'm glad you asked.

First, it would really help if professors would make better assignments that emphasized the conversational aspect of writing academic documents. It's why professors write their own academic documents: first to engage their professional subject matter (they want to learn more about botany, for instance) and then to engage their peers (they want to show off to the scientific community what they've learned about how trees communicate). Let's break this down using this blog post that I'm writing and you are reading.

In this post, I'm writing about writing because writing is my long-time professional interest. I've been studying composition, rhetoric, and literature since graduate school back in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the University of Miami. I've put in the effort because I find this topic rich and rewarding. I've thought long and hard about rhetoric and poetic, and I have a few things to say about them. And the more I have learned, the more I learn that there is to learn. Learning begets learning.

Of course, most of you do not share my interest in and enthusiasm for writing and literature. For too many of you, courses in composition and literature are just annoying hurdles you have to jump on your way to a career in nursing, or computers, or business.

Fair enough.

But this attitude doesn't really help you through this class, and it ignores the reality of a college education. You have signed up for a four-year college degree, which means that you are committed to both a specific major AND a broad understanding of human knowledge. The broad understanding supports the more narrow skills and abilities you learn in your major: nursing, information technology, or business, for instance. A bachelor's degree implies that you not only have learned how to take a person's temperature and draw their blood, but you can also read a medical chart, listen and speak intelligently to scared patients, write down clear, intelligible instructions and comments for a too-busy physician, and use numbers to track the rise and fall of a critical patient's blood pressure. You will have not only the narrow skills that make you a competent nurse, but you will have the broader understanding that helps you recognize, fit into, and work with a wide range of professionals and patients in a modern, complex medical environment. You will have a broader intellectual base that will position you to learn more as you progress in your career. You don't get that broad understanding with narrow, technical training. You get that with a broader college education. Developing a deeper appreciation for that kind of broad, liberal arts education will seriously help you get through college.

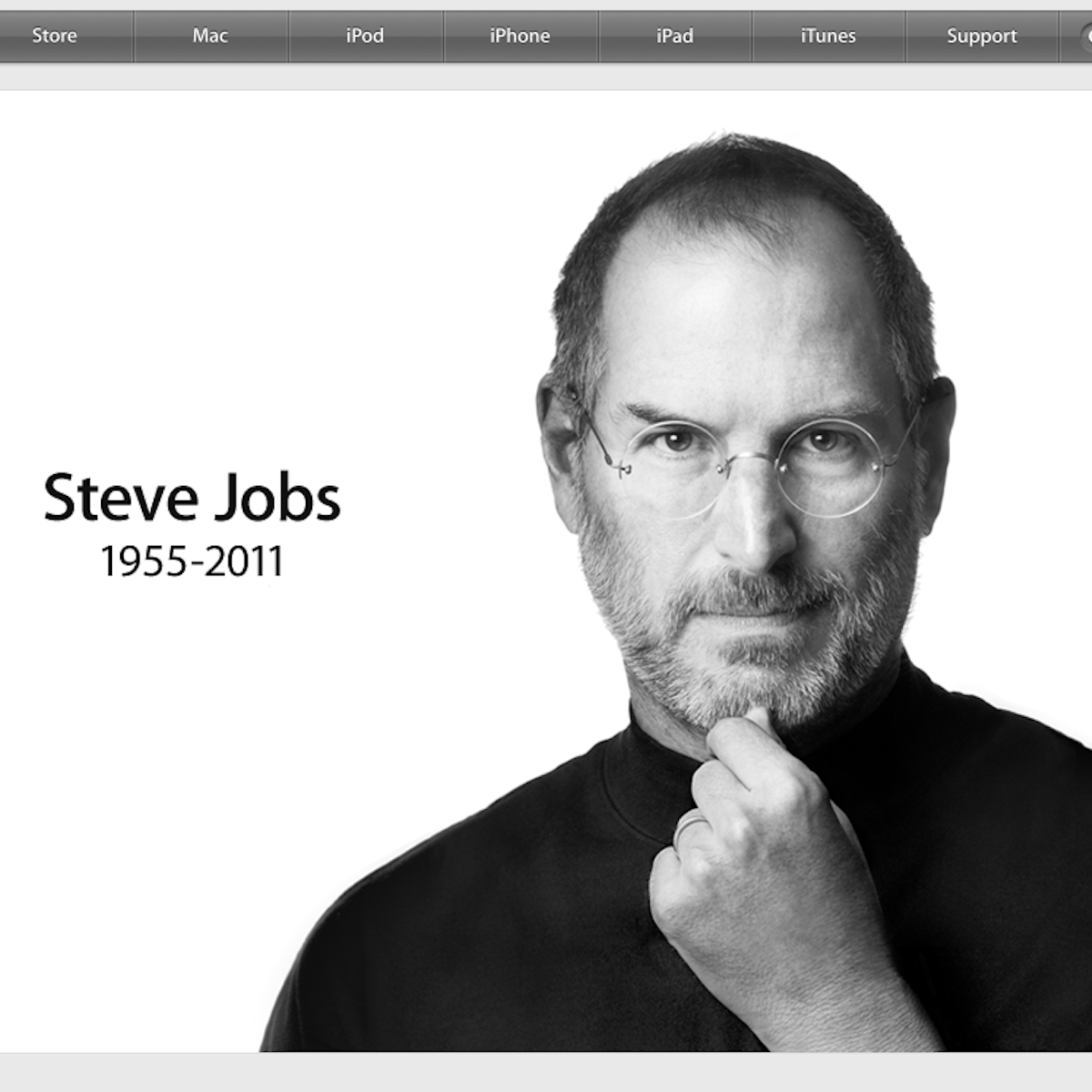

So the biggest benefit of college is learning to learn — to learn anything. And you don't know what will benefit you. In his article "A Tribute to a Great Artist: Steve Jobs" in the Smithsonian Magazine, Henry Adams tells a story about how Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple Computer, was greatly influenced by a class in Chinese calligraphy that he took at Reed College before he became a computer entrepreneur. His innate interests in life and his eventual career focused on technology, and perhaps no one — not even Steve Jobs himself — could see how an artsy-fartsy class in Chinese calligraphy could help him pursue a career in technology, but it did. It helped Jobs re-envision the personal computer with the graphical user interface that changed everything. Then that artistic sensibility helped him later when he founded Pixar, the animation company that he eventually sold to Disney for billions of dollars. If you want to succeed, you need an intense focus (your major) supported by a broad and insatiable curiosity about everything (your liberal education). You need both a wide view and a narrow view. As Iain McGilchrist explains in his marvelous book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (2009), you must use your whole brain: scan the big picture with your right brain and focus on details with your left brain. You must do both. Remember: the world is complex, and everything is connected to everything else. The details don't make sense without the big picture, and there is no big picture without the details. Both are required.

And written and spoken languages are among the most beneficial tools you have for learning most everything intellectual. Language is the tool of choice in college. If you can't read it, you probably can't learn it. If you can't write it down, you probably don't know it. If you don't know it, then you probably can't succeed in class. You must be able to read and write, listen and speak. All are necessary.

Then, you must learn to converse with people about what you know and what you want to know. I'm writing to you now because I want you to understand some things that I've learned over my 50 years of studying writing and doing writing. I think you will succeed better in my class if you understand how to engage the class, and if you succeed, then I succeed. I will have a better time, and so will you.

So learn to engage the material first so that you can learn something, and then learn to engage your audience so that you can help extend that knowledge to others. Talk to each other about something important. That's basically it, and that's basically the most important thing about writing.

So leave me a comment about writing as a conversation. Does that metaphor make sense to you? Does it change the way you think about academic writing? Ask Gemini what ancient Greek rhetoricians had to say about skillful use of language. Converse with me. Converse with your colleagues. Converse with the material you are reading.

Teaching moment:

Have you noticed how I have integrated outside, secondary sources into my own writing? You should notice. Most academic writing expects authoritative support for any claim you make, so when I claim that people today are writing more than at any other time in history, then I support it with hard research – either my own, or more often, that of other authoritative scholars. And when I claim that Steve Jobs benefitted from a college class in Chinese calligraphy, I support my claim with a superbly researched article in the Smithsonian, a recognized, authoritative journal. After all, I didn't know Steve Jobs firsthand, and I've never been to Reed College where he took that class. If I want my claims to be believable, then I should support them with authoritative evidence. You should do likewise in your own academic writing. Save your unsupported claims for arguments at your local bar. Few people there care about sources.

You’re definitely correct when you say most don’t share the same interest and enthusiasm, I fall in that category. Composition and literature have never been a strong suit for me and in turn have become not one of my favorite subjects. However, even though I find it a hurdle to get to my end goal, I’m still trying my best to improve. I will give it my best shot regardless of what is thrown at me, because I have quit before. Thats a mistake I will not make again. Because like you said, you don’t know what will end up benefiting you in the future.

ReplyDeleteI have thoroughly enjoyed your approach to teaching, you incorporate tools from the real world, tools that we will use each day. It is my hope that reading my work does not direct you to suicide though, maybe just an extra margarita while in the Bahamas. I appreciate your guidance to use writing as simply communicating, as you pointed out, you never know what life event may alter your course of action. What Steve Jobs experienced happens to each of us, my take away is cherish each event as you do not know where it will lead you.

ReplyDeleteI remember being asked in middle school, "What is your favorite subject?" Without fail I would always say something along the lines of writing or ELA. While I'm not sure if that's still true, I do enjoy writing and reading still. Though, it still has its ups and downs, like when you mention how students don't always want to write about "anthropology, botany, or zoology" sometimes everyone can find a middle ground to be able to talk about these topics, and not get bored. And you're right, reading and writing, even if it isn't about your chosen major, will help you on a deeper level because of simple knowledge and understanding. Writing to engage and be engaged will make the world turn better, and it will get someone way farther in life because whether they like it or not, the world does revolve around words; reading, writing; and speaking.

ReplyDeleteOne of the most important aspects of good writing is clarity. Always aim to express your ideas in the simplest and most straightforward way possible. Avoid unnecessary jargon and complex sentences that might confuse your readers. Additionally, make sure to thoroughly research your topic. Accurate research not only strengthens your arguments but also enhances the credibility and reliability of your writing. Finally, don't forget to revise and edit your work. Even the best writers need to refine their drafts to ensure their message is clear and error-free."

ReplyDeleteOne of the first steps you must take when learning to write is to be comfortable with writing to others. What comes a bit later than that is being comfortable with writing about subjects outside your usual study, which is what most students like me struggle with. I think you're right in that the way of remedying this is to think about writing as if it's a conversation you're having in real time, whether if it's about what you know or what you want to know.

ReplyDeleteI find that when I am writing on an assignment I enjoy or one where I get to pick the topic I do better than if I am given a subject to write about and don't enjoy the topic as much. I also think the type of paper I am writing has something to do with how I write like a conversation. If I am writing a argument or persuasive paper it is going to be more like a conversation rather than if you were writing an informative piece on something you read in history class.

ReplyDeleteYour approach to teaching writing has been different from any other class I have taken my entire life. I have enjoyed this class and have definitely learned some things that I plan to carry with me. Even though I don't enjoy writing, this class has made me realize how much I didn't understand writing. Thank you for opening my eyes and helping me to become more intrigued with writing,

ReplyDeleteNow that I am in college, I can definitely agree that I don't enjoy writing as much as I used to when I was in high school. That is because the topics that we are supposed to write about in college are subjects that I haven't experienced yet. I feel like I won't be able to relate, and then I would end up sounding not so smart, and that is my biggest fear. But that is where the "biggest benefit of college is learning to learn — to learn anything." You have to be open to learning anything so that you can have a successful college life and a life outside of college when you finish. According to Ancient Greek rhetoricians, particularly the Sophists and later philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, placed great emphasis on the skillful use of language. They believed that the ability to use language effectively was essential for persuasion, argumentation, and public speaking.

ReplyDeleteBy framing writing as a dialogue with ideas, people, and even AI, the relational and dynamic nature of the process has the potential to transform how students engage with assignments. This approach makes writing more accessible and meaningful, supporting it with the natural human inclination toward communication. The idea that students already write effectively in their personal lives but struggle with academic writing due to a lack of connection or relevance is particularly echoed. This gap highlights a missed opportunity in education: helping students see academic writing not as a chore but as an extension of the conversations they are already having. Your example of Steve Jobs’ calligraphy class shows how unrelated learning can fuel creativity in unexpected ways, reinforcing the value of a broad liberal education. The practical advice to treat writing as a conversation, engaging both the subject matter and the audience, shifts the focus from merely fulfilling word counts to fostering genuine intellectual exchange. Encouraging professors to create assignments that emphasize conversation bridges the gap between students’ lived writing experiences and the demands of academic discussion. I also appreciate the teaching moment at the end, where you model integrating authoritative sources into writing. It’s a practical reminder that academic writing isn’t just about expressing personal thoughts but building on a foundation of credible evidence to advance the conversation. The metaphor of conversation does change how I think about academic writing. It reframes the process as an opportunity to connect, explore, and contribute, rather than as an isolated task.

ReplyDeleteBy encouraging students to connect their personal interests to the subjects they study, you effectively illustrate that academic writing can be transformed into a meaningful conversation. Your remark that students are already prolific writers in their personal lives is significant because it demonstrates how they may apply the same zeal and conversational style to academic contexts.

ReplyDeleteSo leave me a comment about writing as a conversation. Does that metaphor make sense to you? Does it change the way you think about academic writing? Ask Gemini what ancient Greek rhetoricians had to say about skillful use of language. Converse with me. Converse with your colleagues. Converse with the material you are reading.

ReplyDeleteWriting as a conversation seems like a good idea, I don't understand much of it but I would be interested in researching it if we utilize it more. The big picture of writing as a conversation is a metaphor I do not fully understand. It changes how I think of academic writing a bit, but not enough to decide to fully implement it. Thank you for trying to make us better ourselves with writting maybe one day i'll look back and thank you again.

I have always seen English composition as "just a hurdle," but your approach to teaching it as a conversation has been refreshing and provides an entirely new perspective on writing. I certainly find more purpose in my writing when I view it this way. Also, viewing college as a place to learn is a new perspective, especially given that jobs require technical and broader training.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting to see your view of writing as a conversation, and I totally agree with it. With you saying that most students already engage in numerous conversation daily, I wonder how students think of writing academically is any different than writing a post or a tweet on social media. Personally, I do think I write more and just do better overall when addressing a topic I favor, but if the topic is unfamiliar and boring (for me), I have a greater time struggling what to write and how to put my message into the writing.

ReplyDeleteI don't have the best history when it comes to writing essays and creating research papers, but I can easily write 3 pages worth of text about my favorite franchises. The way you understand this and encourage your students to write as if it were a conversation is an interesting take that many don't truly understand.

ReplyDeleteLove how you emphasize conversation as a crucial element in writing classes. It reminds me of how writing is often seen as an interaction with ideas and people, much like the way Maddalena's essay highlights the importance of rhetorical awareness in academic writing. When students see writing as a meaningful exchange, rather than just a task, it can truly transform their engagement and the quality of their work.

ReplyDelete